Difficult to Stomach: H. pylori and Gastric Cancer

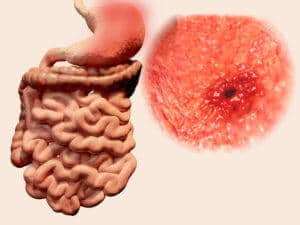

It is well known to most of us that bacteria cause some of the deadliest infectious diseases in humans and animals, but did you know that bacteria can also cause cancer? This is true in the case of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a Gram-negative, spiral-shaped bacterium which colonizes the mucus layer that covers the inner human stomach tissues. The interesting and unique feature of this bacterium is its ability to survive in the highly acidic environment of the stomach.

H. pylori secretes urease, an enzyme that breaks down urea into ammonia, which neutralizes the acidic pH in the stomach, allowing the bacteria to survive in this harsh environment [1]. H. pylori is a common bacterium found in humans, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about two-thirds of the world’s population harbors H. pylori. Most individuals infected with H. pylori do not present any symptoms or develop serious illness, but in some individuals, H. pylori causes peptic ulcer disease. Moreover, it is now estimated that H. pylori accounts for the majority of stomach and upper small intestine ulcers in humans [1–2].

H. pylori secretes urease, an enzyme that breaks down urea into ammonia, which neutralizes the acidic pH in the stomach, allowing the bacteria to survive in this harsh environment [1]. H. pylori is a common bacterium found in humans, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about two-thirds of the world’s population harbors H. pylori. Most individuals infected with H. pylori do not present any symptoms or develop serious illness, but in some individuals, H. pylori causes peptic ulcer disease. Moreover, it is now estimated that H. pylori accounts for the majority of stomach and upper small intestine ulcers in humans [1–2].

How does H. pylori relate to cancer? Cancer is a group of diseases that is characterized by abnormal cell growth and the ability to invade and spread to different parts of the body. Gastric cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer and traditionally was not known to be related to infectious microorganisms. This perception changed in 1982, when two Australian scientists, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, reported the presence of H. pylori in a patient with chronic gastritis and gastric and duodenal ulcers [3]. Further research provided compelling evidence linking H. pylori infections to the development of stomach cancer. In 1994, H. pylori was officially classified as a cancer-causing agent, or carcinogen, by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) – part of the World Health Organization (WHO) [4]. Now it is widely accepted that H. pylori infection can contribute to the development of gastric cancer and of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma [5]. But it should be noted that infection with H. pylori alone does not lead to stomach cancer; other factors, such as genetic susceptibility, are also necessary and important for the development of stomach cancer.

H. pylori is a very difficult bacterium to grow and is microaerophilic, meaning it grows in environments with lower levels of oxygen than are present in the atmosphere. The bacterium is also facultatively intracellular inside the human host, meaning it can reproduce both inside and outside of human cells, making it difficult to treat with antibiotics. There is a huge interest in studying H. pylori among scientists and the pharmaceutical industry because of the rapid emergence of antibiotic resistance to currently available therapies, such as proton pump inhibitors combined with antibiotics like Clarithromycin and Amoxicillin [6]. The only method approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to test the antimicrobial susceptibility of H. pylori is by performing an Agar MIC, following the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines.

H. pylori is a very difficult bacterium to grow and is microaerophilic, meaning it grows in environments with lower levels of oxygen than are present in the atmosphere. The bacterium is also facultatively intracellular inside the human host, meaning it can reproduce both inside and outside of human cells, making it difficult to treat with antibiotics. There is a huge interest in studying H. pylori among scientists and the pharmaceutical industry because of the rapid emergence of antibiotic resistance to currently available therapies, such as proton pump inhibitors combined with antibiotics like Clarithromycin and Amoxicillin [6]. The only method approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to test the antimicrobial susceptibility of H. pylori is by performing an Agar MIC, following the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines.

At Emery Pharma, we are supporting drug discovery companies in evaluating the antimicrobial properties of their test articles against H. pylori using CLSI/FDA-approved microbiological techniques. Many of the H. pylori clinical isolates in our strain collections are confirmed to be highly resistant to current standard antibiotics such as Metronidazole and Clarithromycin. If you want to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of your lead candidates against H. pylori, please contact us today through our website or call us at +1 (510) 899-8814!

About the authors

Kavitha Srinivasa holds a Ph.D. in Microbiology.

Sridhar Arumugam holds a Ph.D. degree in Microbiology and he is the Director of Cell and Microbiology with Emery Pharma.

References

- Sostres, C., Carrera-Lasfuentes, P., Benito, R., Roncales, P., Arruebo, M., Arroyo, M.T., Bujanda, L., García-Rodríguez, L.A. and Lanas, A., 2015. Peptic ulcer bleeding risk. The role of Helicobacter pylori infection in NSAID/low-dose aspirin users. The American journal of gastroenterology, 110(5), pp.684-689.

- Plummer, M., Franceschi, S., Vignat, J., Forman, D. and de Martel, C., 2015. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to Helicobacter pylori. International journal of cancer, 136(2), pp.487-490.

- Marshall, B. and Warren, J.R., 1984. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. The Lancet, 323(8390), pp.1311-1315.

- Anonymous Live flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 1994; 61:1–241

- Rugge, Massimo, Matteo Fassan, and David Y. Graham. "Epidemiology of gastric cancer." In Gastric Cancer, pp. 23-34. Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- Shiota, S., Reddy, R., Alsarraj, A., El-Serag, H.B. and Graham, D.Y., 2015. Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori among male United States veterans. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 13(9), pp.1616-1624.